From the Editor’s desk:

detail courtesy of scholastic.com

Since its founding, the Baltimore City Historical Society has promoted researching and writing about Baltimore City history. Through the Garrett Power led conferences on aspects of the City’s history, the Arnold prize for the best published piece on the City’s past, Mike Franch’s history evenings at the Village Learning Center, and the special recognition given each year to those who promote, research and write about a city whose nicknames run from “Monumental City” to the new "Baltimore: Birthplace of The Star-Spangled Banner," successfully advocated by Society members, the Society makes its voice known and the City’s history come alive.

Currently efforts are afoot to update and redesign the Society’s web site where it is hoped a permanent record of all these activities will be found such as the announcement for next year’s

Joseph L. Arnold Prize for

Outstanding Writing on Baltimore’s History in 2016

Submission Deadline: February 16, 2017

Thanks to the generosity of the Byrnes Family

In Memory of Joseph R. and Anne S. Byrnes the Baltimore City Historical Society

presents an annual Joseph L. Arnold Prize for Outstanding Writing on Baltimore's History,

in the amount of $500.

Joseph L. Arnold, Professor of History at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, died in 2004, at the age of sixty-six. He was a vital and enormously important member of the UMBC faculty for some three and a half decades as well as a leading historian of urban and planning history. He also played an active and often leading role with a variety of private and public historical institutions in the Baltimore area and at his death was hailed as the "dean of Baltimore historians."

Entries should be unpublished manuscripts between 15 and 45 double-spaced pages in length (including footnotes/endnotes). To submit an entry address a new e-mail message to : baltimorehistory@law.umaryland.edu

attach the entry as a document in either MS Word or PC convertible format and illustrations must be included within the main document.

There will be a “blind judging” of entries by a panel of historians. Criteria for selection are: significance, originality, quality of research and clarity of presentation. The winner will be announced in Spring 2017. The BCHS reserves the right to not to award the prize. The winning entry will be posted to the BCHS webpage and considered for publication in the Maryland Historical Magazine.

For further information send a message to baltimorehistory@law.umaryland.edu or call Garrett Power @ 410-706-7661.

Those who wish to better understand the past, perhaps even learn from it, face unprecedented opportunities and challenges associated with the electronic world in which this blog/newsletter is written. Now more than ever we can easily search for, and often find, hitherto inaccessible clues to the past, all with remarkable speed and tantalizing results. Sifting through what we find is another matter, to be sure, taking considerable time and effort to make sense of it all in a meaningful way that not only satisfies ourselves and others who read what we write, but also leaves time for family, travel, and trying to unravel the mysteries of the present, including presidential elections.

Then there is the impermanence of what we find and write about on line. Websites come and go, sources are on line one minute and gone the next, and the paper trail to which the electronic world hints as our next stop becomes increasingly inaccessible as funding for archives and archival staff dries up and much of the remaining paper substance of history disappears altogether into temporary warehouses, landfills and incinerators.

In this issue of the Baltimore Gaslight, the attempt is made to salvage some of what has been written on line about the City’s past, accompanied by a new story inspired by a letter sold on Ebay. The stories are based on what can be found at the moment online and offline in threatened, woefully underfunded, understaffed, repositories of paper and photographs.

The irony, of course, is that this blog too may not survive to be mined by future generations. As the creators of Wikipedia well know, it takes money to keep the electronic world healthy, dynamic, and above all, accessible. All that those of us who ‘blog’ can do is to continue to research and write, leaving it to Chance[1], that someone will create a permanent, fully endowed, freely accessible, and user interactive, electronic repository for the product of our labors.

A year ago I assumed the editorship and became the publisher of the Baltimore Gaslight. In addition to trying to meet a high editorial standard set by Lewis H. Diuguid, former Washington Post correspondent and the first editor, I hoped to provide a permanent record of public interest in the history of Baltimore City, asking readers and members to provide essays on their current research and writing interests, and thereby stimulate further work on neglected aspects of the City’s history, including lost neighborhoods. The objective was not to compete with other publications, both in print and electronic, but to provide short stories (well documented) of interest that carry us back in time to people and places in the city, stories that not only enlighten us, and entertain, but encourage us to want to know more, and to retain those reflections in a permanent, ‘indexed’ way that we can easily reference and build upon.

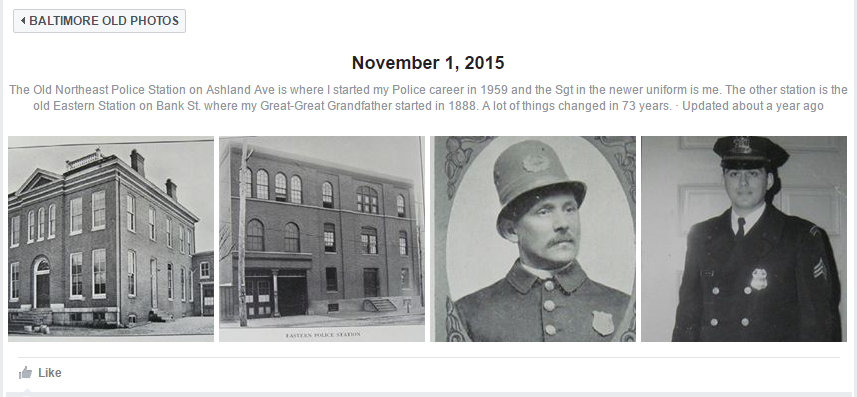

Often it is images that trigger our interest in the people and places of Baltimore. The historical images on such Facebook sites as Baltimore History- Baltimore City Historical Society and Baltimore Old Photos are of good examples. The stories behind those photographs deserve a permanent platform for fuller explanation and access, especially for those who would like to move beyond the initial excitement of discovery and memory that historical images inspire.

Photograph of Carnegie Hall at Morgan College (now Morgan State University) by Jackson Davis, 1921 November 3. Courtesy University of Virginia, 330943.

Some who post on the Facebook pages, such as Eli Pousson, do provide further commentary through websites from which the images are drawn. For example this photograph of Carnegie Hall, Morgan College on the Baltimore History- Baltimore City Historical Society Facebook page leads to an in depth study of civil rights in the city on a Baltimore Heritage web site.

Similar treatment should be given an album entry in Baltimore Old Photos for November 1, 2015, focusing attention on the police, inhabitants, and the neighborhoods encompassed by the Northeast district.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/779324542159457/photos/?filter=albums

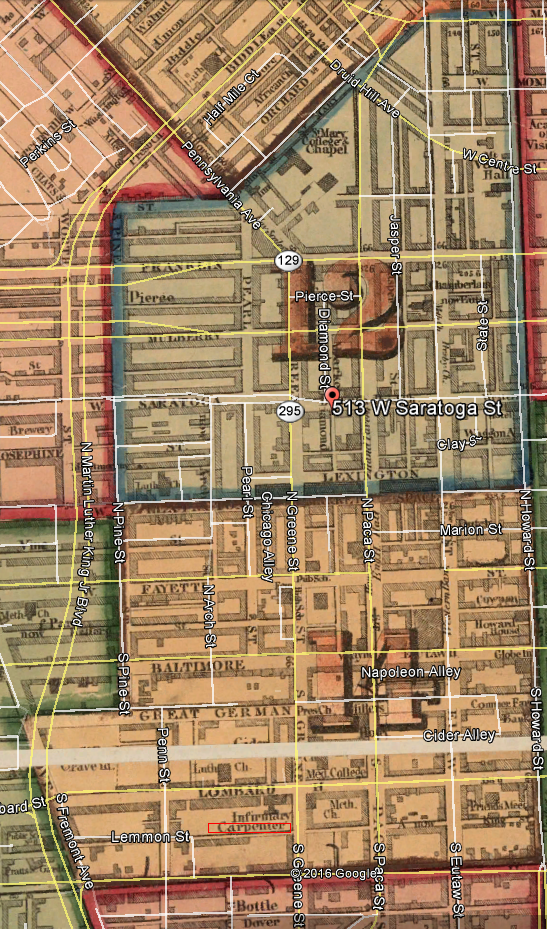

The outlines of the Northeastern Police district

are shown in a detail from this 1880 map (editor’s collection).

The original police station for the Northeastern Police district is now owned by Johns Hopkins University, and is today the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics at 1809 Ashland Avenue.

Hopkins Berman Institute Of Bioethics

the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics at 1809 Ashland Avenue

The early police dockets for the Northeastern district which contain a running narrative of neighborhood events that are not all criminal, are available at the Maryland State Archives:

BALTIMORE CITY

POLICE DEPARTMENT

(Criminal Docket, Northeastern District)

1876-1878, 1900-1952, 1956-1959

C2110

Series Description

This series of Criminal Dockets, Northeastern District was maintained and compiled in whole or in part while the Baltimore City Police Department was a state agency. For a general introduction to the history of the Baltimore City Police Department, see http://guide.mdsa.net/series.cfm?action=viewSeries&ID=sh248. Also, for additional information, see the following privately maintained website: http://wayback.archive-it.org/2504/*/http://www.baltimorecitypolicehistory.com/.

In preparing this edition of the Baltimore Gaslight, I came upon another blog of Baltimore history that is no longer active, and may eventually disappear from the airways like many other blogs and websites. The domain name, charmcityhistory.com, like that of Yahoo’s GeoCities, is already owned by some entity offshore, and is no longer linked to David Mantione’s http://charmcityhistory.blogspot.com.[2]

As a service to our readers, the first section of this edition of Baltimore Gaslight is devoted to a review of what was published in http://charmcityhistory.blogspot.com. In addition, two posts relating to the history of the police in Baltimore are reprinted here as complements to a new article on Detective Tom Gorman, one of the first police detectives appointed to the newly reorganized Baltimore Police force (1858) whose duties took him all over the city, including the Northeastern District.

In the first and second issues of the 15th volume of the Baltimore Gaslight, I was overly optimistic with regard to when some articles were scheduled to appear, and even doubted at times that this blog would last more than a year. I have concluded, however, that as long as there continues to be an interest in the approach to the history of Baltimore City as reflected here, I will continue to publish the topics previously announced.

For example the Now and Then column, will return in a future issue with an essay on the Johns Hopkins Colored Asylum on West 31st Street, its ‘inmates’ (a term used by the U.S. Census Bureau), and its neighbors across the street.

Recently travel in New Zealand and Hawaii has also brought to my attention the neglected stories of three wartime connections to Baltimore,

- a mother from New Zealand, working as a maid in Baltimore whose son died in the Dardanelles during the First World War,

- a baker’s assistant, born and raised on Lombard street, who took some of the most important photographs in the history of the Battleship Missouri and whose parish has disappeared without a trace, save a once impressive Roman Catholic church,

- a New Zealand born graduate of City College who died in Vietnam, and whose name is carved into two walls of remembrance, one in Auckland and the other in Washington, D. C.

Also I will follow through on Is There a Doctor in the House, a story about an MD/inventor/lyricist, Dr. David Newton Emanuel Campbell who lived and had his offices on North Carey and McCulloh streets. In the meantime, the best site to begin any study of Doctors who practiced, or were educated in Baltimore prior to 1920 is Medicine in Maryland, a website created and maintained by Nancy Bramucci Sheads.

I encourage readers and members to submit essays of their own to baltimoregaslight@gmail.com, and to communicate with me by the messaging system you will find to the right just below the masthead on this blog.

I am embarrassed to admit that I thought no one was using the messaging system, and thus not interested in this newsletter/blog until I thought to check the spam folder in the email account created for that form. The Tom Gorman essay, inspired by another set of images on Ebay to which I was alerted by a reader, is the result.

Be sure to follow the activities of the BCHS on the web site, http://www.baltimorecityhistoricalsociety.org/ where you will find a calendar of events relating to the city’s history and information on how to join the society. The Society needs your support.

If you have a story to share about neighbors and their neighborhoods, or any other short narrative (500-700 words) related to the history of the city, send it to baltimoregaslight@gmail.com. Contributions are welcome, as are suggestions for future issues of the Baltimore Gaslight. Note that if you include graphics with your submittals, be sure to cite sources. Note also that if you place your graphics within the text of your essay using Word or a generic word processing program such as that provided by Google Drive, it will make it much easier to publish in this newsletter/blog.

Until next time …

Ed Papenfuse

Editor, and former State Archivist of Maryland

From The Charm City History Blog:

As a service to the readers of Baltimore Gaslight a synopsis of the table of contents of http://charmcityhistory.blogspot.com is provided here along with a reprinting of two posts related to the history of the Baltimore Police Department. The essay titles are hyperlinked to the original entries.

"A Little Treasure Chest from Baltimore's Attic"

Table of Contents:

The Cost of Breaking the Law in Baltimore -

125 to 200 Years Ago

By David Mantione

Baltimore City Hall (c1900)

Detroit Publishing Company

(Courtesy: Shorpy.com)

One would be surprised as to what you might get arrested for in violation of Baltimore City Ordinances between 125 and 200 years ago in Baltimore City. Public law in early Baltimore City was written and enacted in response to the pressing issues of the day (health, safety, wrongs against individuals and public property) as was the case in many developing cities within the United States and around the world. Current Baltimore City laws and ordinances have citations deriving from City Code as far back as 1879.

What follows is a collection of offenses from the period of 1801 to the 1870s, along with associated fines for violating the ordinance or code. It has been determined from actual Baltimore City Ordinance of the period or from court judgments and/or arrests as noted in Baltimore Sun legal articles. So as to impress upon today's reader the magnitude of the fine, each of the fines for offense are indicated by value in today's U.S. dollar.

1801 (as noted in Ordinances of the Corporation of the City of Baltimore)

- Driving a carriage, caravan, wagon, sleigh, cart, etc in the middle (as opposed to the right side) of the street - FINE, $14

- Cock fighting of any kind within the City Limits - FINE, $271

- Gun or pistol which is willfully and needlessly shot or discharged within the City - FINE, $68

- Bringing damaged coffee, hides or other damaged or infected articles into the city limits, by land or water - FINE, $4,070

- Operating the performances or exhibitions without a license (See below, for license cost): - FINE, $13,565

Licenses were required for the following: Circus or theatrical exhibition - $109 / performance; Rope or wire dancing, or puppet shows - $136 / week; Musical parties for gain - $68 / week; All other public exhibitions - $27 / week

1840s (as noted from Baltimore Sun Public Notice, Court Judgments)

- Washing salt sacks in a tub placed under a pump in public - FINED, $37 plus costs

- Throwing rubbish into the street and permitting it to remain there - FINED, $22 plus costs

- Permitting wood to remain upon a wharf longer than 2 days - FINED, $5.50 daily / foot of ground

- purchase or sale of wood without a license - FINED, $44 / each cord sold

1850s (as noted from Baltimore Sun, Public Notice of Court Judgments)

- Throwing stones in public - FINED, $27

- Running wagons without license numbers - FINED, $27-$50

- Improper conduct in the presence of ladies - FINED, $121

- Throwing a nuisance in the street - FINED, $27

1860s (as noted from Baltimore Sun, Public Notice of Court Judgments)

- Allowing a ten-pin alley to be used after 11 o'clock at night - FINED, $252

- Exposing unsound meats for sale - FINED, $504

- Bathing in the Jones Falls - FINED, $17

- Boys were arrested for jumping upon one of the Philadelphia Railroad cars while in motion - FINED, $17

- Running against and breaking a city lamppost - FINED, $85

- Throwing nauseous liquors on the street - FINED, $85

- Immoderate driving in the street - FINED, $85 plus costs

- Gambling on Sunday - FINED, $85 plus costs

- Permitting gambling on premises - $510 plus costs

- Carrying on a distilling business on McElderry's wharf without a license - SENTENCED TO PAY FINE OF $3,236 AND IMPRISONED UNTIL PAID. [Of interest: Within 6 months, the convicted, Thomas Carr, received a pardon from the President of the United States, which remitted the fine and he was immediately released]

1870s (as noted in Ordinances of the Corporation of the City of Baltimore or Baltimore Sun)

- Killing or attempting to kill, or in any manner injure or molest sparrows, robins, wrens, or other small insectivorous birds in the city of Baltimore, to include their birdhouses - FINE, $85 per offense

- Playing cards on Sunday - FINED, $24

- Carrying a concealed razor on his person - FINED, $72

These are in interesting contrast to EXISTING ordinances within the City of Baltimore:

- Tossing, throwing, flinging any object capable of being thrown or used as a projectile (excluding paper wrappers) on the playing field or arena, official or any member of the team at a sporting event - FINE, up to $1000 or imprisonment up to 12 months (misdemeanor)

- Playing, singing, or rendering the "Star Spangled Banner" anywhere publicly in the City of Baltimore, except in its entirety in composition, separate from any other melody. Likewise, it cannot be played for dancing or as an exit march. - FINE, not more than $100 (misdemeanor)

- Sell, give away or dispose of a "toy cartridge pistol" within the City Limits of Baltimore - FINE, $10.

- To discharge or fire a "toy cartridge pistol" - FINE, $2.

- Unauthorized by any person not of the Department of Public Works within the City Limits of Baltimore to remove recyclable materials from designated containers without approval from the owner or operator of the recycling operation - FINE, up to $500 (misdemeanor)

"Reddy the Bull" Predicted Baltimore Motorists' Disgust in Traffic Lights

By David Mantione

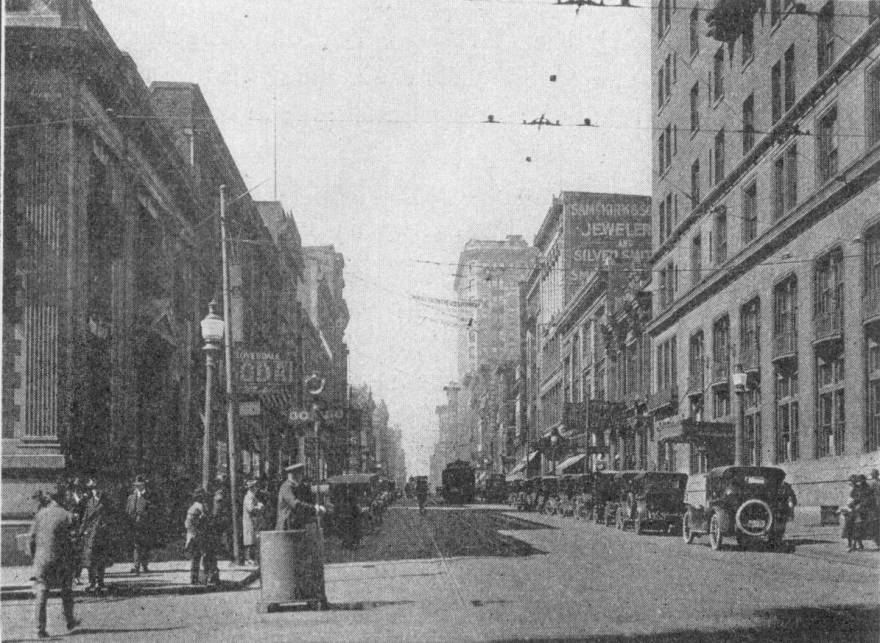

City Traffic, Early 1920s

Within years of the automobile being introduced to Baltimore City streets, the issue of traffic had become a major problem where both patrolmen and/or traffic signals were used to control movement at congested intersections. Besides cars and trucks, traffic included street cars (vehicles traveling on rails) and horse-drawn vehicles. While they all obeyed a general principle of staying to the right on two-way roads, beyond the confusion at busy intersections, it was becoming outright dangerous.

Baltimore City Policeman with

Semaphore, circa 1920

(Courtesy: Kildruffs.com)

As was the case in many bustling cities of the day, at first, whistle blowing and arm waving patrolmen attempted to provide order to the chaos. As early as April 1915, the Baltimore City Police Department had traffic police officers operating 'newfangled' signals upon long poles (or semaphores) having narrow paddles which were painted red on two sides with a bold white "STOP" - they were first trial implemented at the corner of Park Heights and West Belvedere Avenues. Traffic policemen operating semaphores were widely used for a period of five years and often removed depending on the perception of their merit as opposed to the sole whistle and wave of patrolmen.

Gen. Charles D. Gaither

Baltimore City Police

Commissioner (1920-1937)

On June 1st, 1920, a man by the name of Brigadier General Charles D. Gaither, previously commander of the First Brigade, Maryland National Guard began his duties as the Governor-appointed first Baltimore City Police Commissioner. Called "The General," he took Baltimore City traffic seriously and would personally drive through downtown city streets observing the manner in which traffic was handled, especially during rush hour.

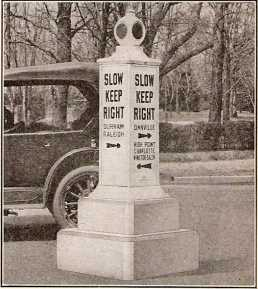

By July 1921, under his direction, the Police Department placed fourteen six feet high "lighthouses" on concrete bases which were intended to warn motorists of dangerous curves and bends at night. The flashing lights in the lighthouses were fueled by acetylene tanks (see photo, below and left) - red flashing indicated places where people had been killed, yellow for dangerous curves or bends where caution must be exercised, and green was for danger at intersections where slow, careful driving should be exercised to the right.

The earlier days of traffic lights and warnings resulted in disgruntlement by drivers and even beasts. Prior to placing the traffic lights on streets with protective bases, they were continually run over by motorists refusing to stop. On October 16, 1923, the Baltimore Sun reported that a certain Jersey bull by the name of Reddy had created a riot in the middle of the congested intersection of Bryant and Pennsylvania Avenues while being led to slaughter. A heard of 40 bulls were being driven down the avenue where automobiles stopped in obedience to a blinking red light, but not Reddy who saw it as a challenge and proceeded to charge it. In the charge, a truck struck and broke its leg before he could reach his "enemy." Unfortunately, agents of the SPCA needed to kill the Reddy earlier than his originally intended fate.

Acetylene Traffic Beacon

General Gaither refused to bring "automatic" electric traffic signals to Baltimore City until the Fall of 1925 since he felt that devices on the market prior to then were inefficient in regulating and safeguarding traffic, effectively still in experimental stages. On St. Patrick's Day of 1926, all semaphores at congested intersections between the north-south Gay and Greene streets and east-west Center and Pratt streets were replaced by automatic electric signals, interestingly controlled by one manned traffic tower - all changing at exactly the same time. The Baltimore Sun further reported that thoroughfares like Cathedral and St. Paul streets and Mount Royal, North and Pennsylvania avenues would be operated independently by a traffic tower on each thoroughfare controlling all signals on that street.

Native Baltimorean, Charles Adler, Jr. (1899-1980) and Sound-activated Traffic Light - Adler Invention

Automatic signals were a change for motorists as they were used to patrolmen hesitating changing a semaphore against an aggressive driver. In contrast, with automatic signals, drivers would know that the signal won't hesitate and that drivers in the opposing direction would move the instant they saw their green signal. Savings were envisioned from reduced manpower, yet for a period policemen were stationed at intersections until motorists and pedestrians were educated to the necessity of observing the signals. Initially, the colors used were RED for stop, WHITE for change, and GREEN for go.

While these traffic lights were "automatic" to motorists, they were still controlled by a patrolman located in a tower. True automatic traffic signals were actually invented by a gentleman by the name of Charles Adler, Jr. who was native to Baltimore. An avid inventor, he invented a sound-activated traffic light (see figure, above, right), pavement traffic light sensors, and a list of many other inventions. For all those motorists passing through Baltimore City streets, beware of camera activated ticket lights. Charge those traffic lights like Reddy the Bull and, while you won't meet his similar fate, you will be certain to receive a citation - you just won't have Charles Adler or General Gaither to blame for it. (Sources: Baltimore Sun Newspaper articles, and Kildruffs.com)

Baltimore Constable and Police Detective

Thomas W. “Tom” Gorman (1821-1863)

A letter sold on Ebay, 2016[3]

On a Sunday morning in January 1859, Frank Thompson, a visitor to Baltimore from Charlestown, Massachusetts wrote a letter to his wife Ruthie, describing the adventure of his train ride from home to the President Street station. The first three legs of the journey were very pleasant. He was accompanied by some local notables and acquaintances from home, stayed overnight in New York, where he smoked and talked into all hours, and went on to Philadelphia the next morning. From there to Wilmington Delaware he still had people he knew to talk with, but after Wilmington, “being alone,” he moved to the smoking car, the last car in the train, where he encountered men of a different sort:

Soon after [I got there] much to my surprise some 15 to 20 of the worst looking fellows came & began to carouse, having a bottle [of] whiskey. They soon began passing around said bottle (without glasses). I declined the honor of a drink as politely as possible, fearing to offend. Soon after the leader of the crowd came & took a seat next to me & commenced conversation by informing me that one of the number (who at that moment was very drunk) had just been discharged from custody on charge of murder in Phila, the evidence not sufficient to prove it, although I have no doubt he was guilty. My friend also informed me that he was one of the Balto police and a great scoundrel … On the first chance I left the Car, but not before my friend, who informed me that his name was Tom Gorman, assured me that if I ever got into any scrapes in Balto, to send for him ...which I promised to do. That nice fellow (the conductor, afterwards informed me) was [of] a delegation of the celebrated “Plug Uglies’ club of Balto who had been on to Phila to escort their friend (the murderer) back to Balto[4]

Frank made it back safely to Charlestown to his wife and young daughter.[5]

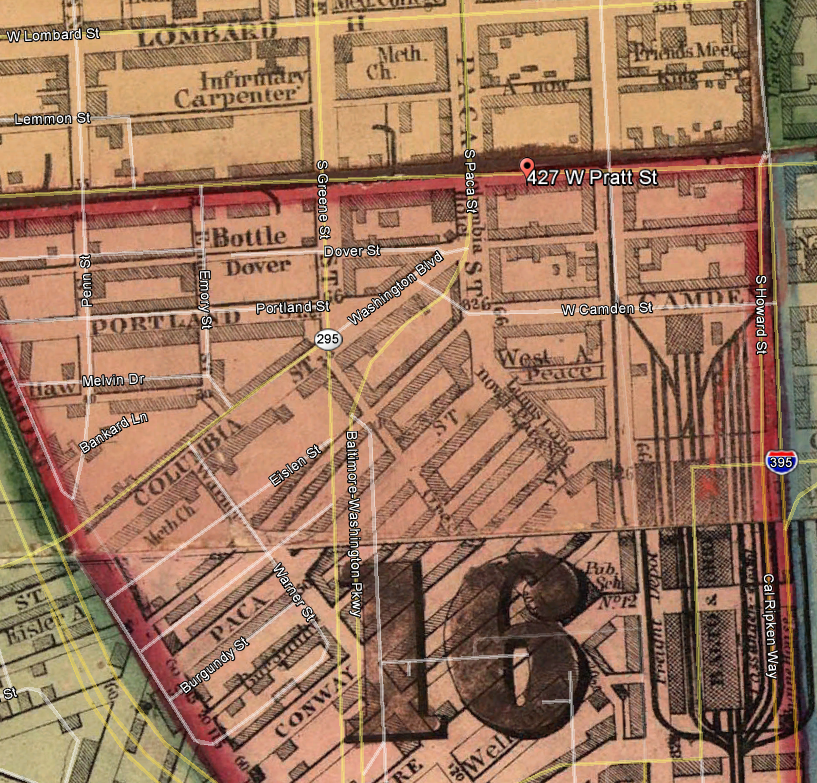

Carpenter’s Alley in 1851 in the 14th Ward

From the revised Thomas Poppleton Map

“Tom” Gorman, born in Pennsylvania, first appears in the public records of Baltimore City as a constable (1848)[6] and then as a concerned citizen. In 1850, according to the city directory, he lived at 204 Saratoga Street in the 12th ward (what today is 513 West Saratoga), and is identified as a police officer. In 1854 he dropped his protest over a steam mill being erected on Carpenter’s alley, an alley that ran from Fremont to Howard street in the 14th ward of Gorman’s day, but which today survives only as a fragment of its former self called Lemmon street.

From the revised Poppleton map of Baltimore, 1851-5,

with white and yellow lines depicting current streets, and large numbers indicating the ward.

By 1859, Tom Gorman was living at his restaurant at 317 West Pratt Street in the 16th Ward, what today would be 427 West Pratt, and working as a police detective out of an office on Pleasant Street in or near City Hall. He had been appointed one of the first city-wide police detectives in 1858, and had clearly shown his patriotism by gaining city permission to erect a flagpole near his restaurant on the corner of Pratt and Paca. In all likelihood his restaurant was a center of political activity for both the 14th and 16th wards.[7]

Baltimore City Archives, BRG32, series 1, 1856, item 857

Baltimore City Archives, BRG 32, Series 1, 1856, item 259

In order to become a detective, Tom Gorman had to post an $800 bond, a fairly steep entrance fee for his new job. An interesting story may lay behind who were his sureties.

Baltimore City Archives, BRG 16, Series 1, item 429

Tom Gorman did not appear to make much money as a constable or a detective. His name appears on a constable’s payroll for 1856, and is said to appear on the payroll for 1860 which has gone missing since it was inventoried by the Works Progress Administration in the late 1930s. In 1856 his salary was $41.66 a month or $500 a year. What he was paid by 1860 as a plainclothes detective was $10 a week or $520 a year,[8] not much of an increase, but he supplemented his income at his restaurant, and perhaps in other ways, some of which may not have been legal.

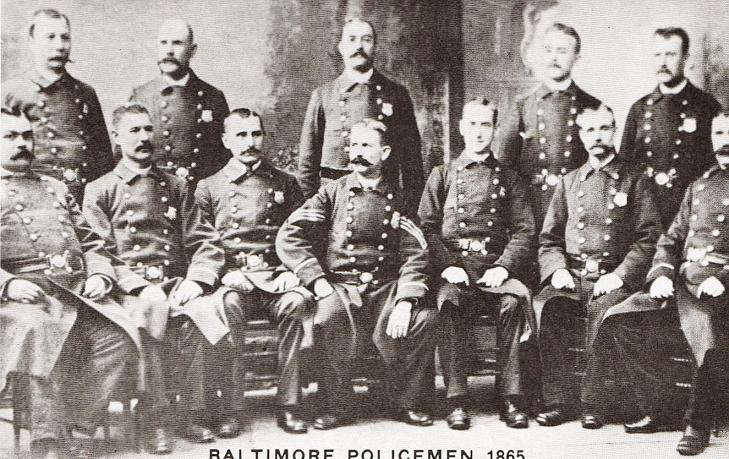

1860 was a tumultuous year for the Baltimore City Police department. That year the State conducted an extensive investigation into voter fraud and intimidation by the dominant political party in the city, the Know Nothings, that may have been abetted by the Police.[9] According to a history of the Baltimore Police published in 1888,

the [police] force was gradually filled [after 1857] with " Know-nothing" recruits, who, instead of maintaining the peace, became willing tools of violence and riot. Thus, in many instances, the men sworn to enforce an observation of the law became the chief instruments in subverting it. For several years the city was given up to a mob. At every election, riot swept many quarters of the city. Because of these facts a committee of the Reform party in 1859 drafted a number of bills, known as the "quot;reform bills," and among these was the police bill.[10]

As civil war approached and pressures increased for Maryland to secede from the Union, Detective Gorman garnered considerable press, local and national, for his success at apprehending criminals. In his first year as a detective he arrested a forger of a $384.75 bank draft who posed as traveling lightning rod salesman and who was found by Gorman in bed with his male accomplice at Columbia House at the corner of Pratt and Paca, not far from Gorman’s restaurant.[11]

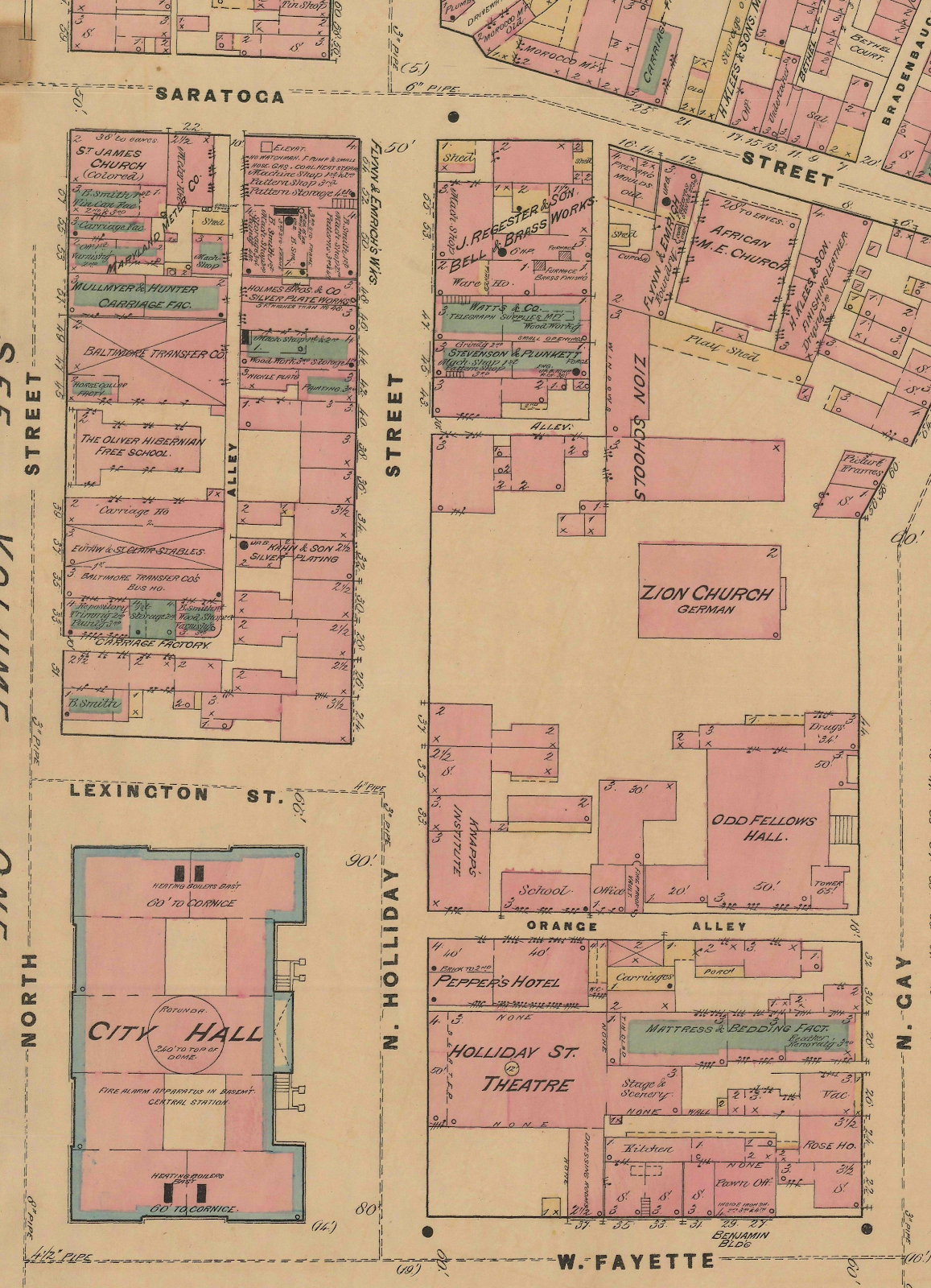

Odd Fellows Hall on North Gay Street, 1864

Detail from the Sanborn Insurance Maps of Baltimore, 1879/1880

In February 1860, Detective Gorman gained national recognition for foiling the attempted robbery of Thomas Wildey[12], founder of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, a wealthy organization that had built a large and impressive building not far from City Hall and Detective Gorman’s office. The National Police Gazette, published in New York, reported in its February 18, 1860 issue that on February 10 Grandsire Wildey (in his late70s) was returning home

From the Holliday Street Theatre, and as he was stepping into a city railway car, an attempt was made by two notorious pickpockets to rob him. The “old king,” however, was a little too wide awake, and detected the hand of one of them in his pocket, and called for aid, when the fellow was nabbed by Tom gorman, who happened to be on hand. He proved to be -- Brown, one of the most noted pickpockets and villains in the city. The other was Reese, especially noted in the same line, and the man who personated Flim Flam, and aided his escape from the County prison some time ago. This villain was supposed to be in jail, but it seems he has been discharged on bail, and allowed to continue his course. Both of these men belong to the Holliday street party, and it was near that den that the robbery was attempted.[13]

In that same issue the Baltimore correspondent goes to great length to describe the tribulations of the police department suggesting that Tom, as a member of the old guard would have been displaced by a new appointment under the recent law that placed the police department under the control of the State, if the Mayor had not refused to recognize the new board and kept the old police force at work.

It seems that Detective Gorman made more than one trip to Philadelphia to retrieve criminals. In August 1860 he brought back a burglar, Charles Everett, alias White, alias the Doctor, a fugitive from justice accused of burglarizing several Baltimore establishments including the auction house of Samuel H. Glover, the bacon house of Messrs. McConkey & Co., and the store of Mr. White. Everett was sent to jail to await the action of the grand jury.[14]

On November 28, 1860, Deputy Marshall Gifford, Detectives Stevens and Gorman, and policeman White investigated a robbery of $30 worth of clothing at Archibald Stirling’s on Hillen Road. They were able to find the tracks of the gig (a vehicle with two wheels drawn by a horse). They found the tracks

on the Harford road to Aisquith st. and thence along the wall of Greenmount cemetery to the tunnel under the York road, near that point. It appears that there was so much water in the tunnel that the thieves concluded it was not a safe place, and went up on the hill near the cemetery and concealed the clothing in a sand bank, where it was all found. The gig was found some distance up the York road, where it had been left after burying the stolen clothing. No clue has yet been obtained as to who were the perpetrators of the robbery.[15]

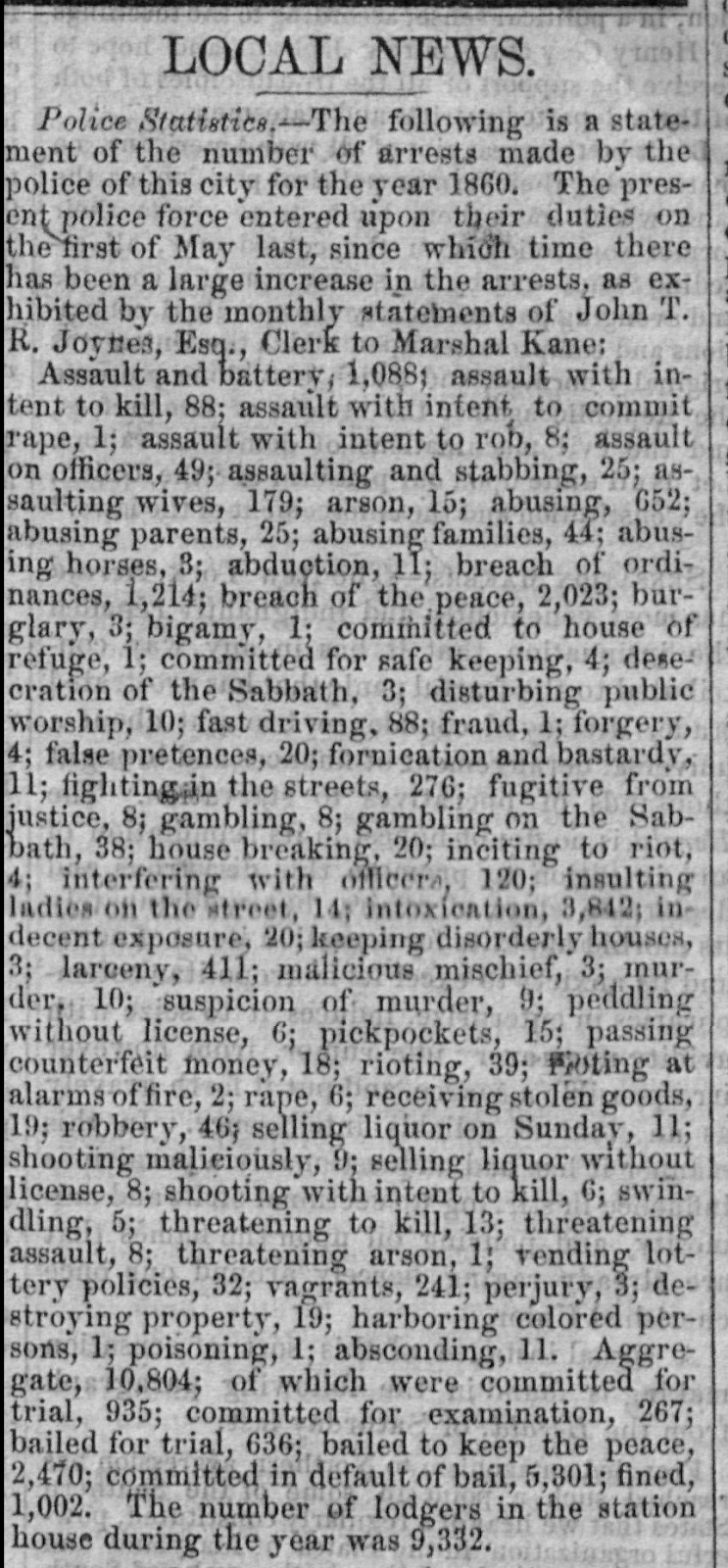

Marshall Kane's Crime Statistics for Baltimore for 1860, Baltimore Clipper, January 1, 1861

It would appear from the Baltimore Clipper, that until late June of 1861, Detective Gorman continued to pursue pickpockets and other robbery suspects, but those accounts stop suddenly with the arrest of Marshall Kane and the Union interests take over the Police Department.

Kane and then the Mayor, George William Brown, were thrown into prison and deported from the City without benefit of an appearance in court (they were prevented by the military from availing themselves of Habeas Corpus). As Mayor Brown later recalled:

On the 10th of June, 1861, Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, of Massachusetts, was appointed in the place of

General Cadwallader to the command of the Department of Annapolis, with headquarters at Baltimore. On the 27th of June, General Banks arrested Marshal Kane and confined him in Fort McHenry. He then issued a proclamation announcing that he had superseded Marshal Kane and the commissioners of police, and that he had appointed Colonel John R. Kenly, of the First Regiment of Maryland Volunteers, provost marshal, with the aid and assistance of the subordinate officers of the police department, the police commissioners, including the mayor, offered no resistance, but adopted and published a resolution declaring that, in the opinion of the board, the forcible suspension of their functions suspended at the same time the active operation of the police law and put the officers and men off duty for the present, leaving them subject, however, to the rules and regulations of the service as to their personal conduct and deportment, and to the orders which the board might see fit thereafter to issue, when the present illegal suspension of their functions should be removed. [16]

Detective Gorman was out of work After having his successful arrests recorded on the front pages of the Baltimore Clipper ten times between January and May 1861 and having been sent by Marshall Kane only a few days after the April 19th riots to report on the retreat to Harrisburg of the Pennsylvania militia, he was relegated to hiring himself out as doorkeeper and private detective at the Maryland Institute fair where he was attacked by three rowdies.[17]

Is it no wonder that he took to drink, was arrested for brawling, and for his vocal support of the Southern cause?

The last the public in Baltimore heard of former police detective Tom Gorman was in flight:

BALTIMORE, MD., May 25 [1862]

THE excitement and exasperation of feeling that has been smouldering in this city ever since the memorable scenes of April, 1861, culminated yesterday in acts of violence and serious breaches of the peace….

In the course of the morning, Thomas W. Gorman was observed standing in the portico of the City Hotel, when a crowd started in pursuit, but they were not quick enough, for he managed to escape by a private entrance.[18]

Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington, North Carolina

What happened to Detective Gorman next is not known for certain, but it is likely that he went South to join the Confederacy as did his chief, Police Marshall George Proctor Kane (1817-1878), later the 26th mayor of Baltimore (1877-1878).[19] That he was dead by August 1863 in Wilmington, North Carolina, is suggested by an undocumented tombstone.[20] His family remained in Baltimore. His son William, according to the 1870 census, became a teacher, and Fannie, Tom Gorman’s wife, who lived for at time with her son, never re-married. She died in 1902 at the age of 79 and was buried in Western Cemetery as was her daughter-in-law the year before. In her later years she may have lived alone near her daughter-in-law, also named Fannie, with one or the other of them earning a living as a seamstress.[21]

In all Tom Gorman’s life in Baltimore encompassed one of the more raucous and strained times in the City’s history, one in which the city was ruled by an unruly democracy and served, perhaps, by a not always honest constabulary. Jean H. Baker, William Evitts, and Tracy Matthew Melton have provided excellent historical contexts for Tom Gorman’s world in the years leading up to the Civil War, and are required reading for guidance in understanding the politics of that era.[22] The surviving evidence of Tom Gorman’s life provides additional and personal insight into the day to day experiences of those who lived during those times, helping us to better understand the rhythm of city life in the context of where people lived and worked.

That we know as much as we do about Detective Tom Gorman’s life in those divisive times is due to fragmentary evidence scattered in many places, some of which is only available on the internet, and all of which is threatened by the instability of the electronic world and the inadequate care of underfunded, understaffed, and in some cases, failing archival institutions.

[1] Whim and our grandson

[2] The aim of http://baltimoregaslight.blogspot.com is to publish on line in permanent electronic form, stories about Baltimore's past similar to those in http://charmcityhistory.blogspot.com, but I am fearful that they might disappear someday without a trace, unless a way can be found to perpetuate them through institutional commitment (that sounds a bit like the mental hospitals of old, but what I mean is Public Archives or Historical Society financial commitment). It would be a shame if all the nicely illustrated and documented essays in this blog and http://charmcityhistory.blogspot.com were to disappear. I once built a fairly extensive collaborative history site at GeoCities (Yahoo's brilliant effort at offering ‘free’ websites to researchers) but when that folded on short notice all that my students and I had accomplished to date on that site disappeared into the ether. The same is true of a more recent effort, ecpclio.net, which I had hoped would continue to the benefit of scholars working with private and public records in Maryland. Perhaps the third time’s a charm with this blog?

[3] image courtesy of David Chesanow

[4] quotation courtesy of David Chesanow, transcribed from the image provided on Ebay

[5] Considerable details about the Thompson family can be found on Ancestry.com. I wonder if any of the rest of the family correspondence has survived?

[6] The Baltimore Sun, 1849/09/15, p. 2

[7] In the 1860 census Detective Gorman, age 39, is living with his wife Annie (Fannie/Fanny?), age 35, and two sons, John, age 11, and William, age 15, in the 14th Ward. The ward designation is probably an error. The restaurant was just across Pratt street in the 16th ward. The 1850 census, when he was living in the 12th ward at 204 Saratoga, Thomas W. Gorman was listed as a white male born in Pennsylvania, age 27, with a wife Fanny, age 26, and two sons, William, age 4, and John age 1. See Ancestry.com for images of the census schedules. In order to translate the street addresses of the 1850s and 60s to their location today, see: R. L. Polk & Co’s Baltimore City Directory for 1887. It appears to be the only year that the city directory provided conversion tables by street name of old addresses to new, with old numbers first and new numbers preceded by *.

[8] de Francias Folsom, Our Police ..., 1888, p. 29. Folsom’s history is available on the web at https://archive.org/details/ourpolicehistory00fols. For an extensive and informative study of the Baltimore Plug Uglies, see Tracy Matthew Melton, Hanging Henry Gambrill, The Violent Career of Baltimore’s Plug Uglies, 1854-1860, Baltimore: The Maryland Historical Society, 2005.

[10] More needs to be done with investigating the individuals mentioned in the legislative investigation of the police in Baltimore and the court cases that followed the act transferring control over the police to the State. The court cases are to be found at the Maryland State Archives.. For an extensive study of the Plug Uglies and Police involvement at the polls see Tracey Melton … and Walker Lewis. For the best histories of Maryland in this period including Baltimore politics, see Baker, Evitts,

[11] Baltimore Sun, 1858/03/05, p. 1. In 1859 Columbia house is listed in the 1860 City Directory as: BLANCK JOHN, Columbia house, 471 w Baltimore. From the city directories it appears that Columbia House moved around to different locations suggesting that it was not the most reputable of boarding houses or hotels.

[13] The National Police Gazette, February 18, 1860.

[14] Baltimore Sun, 1860/08/27, p. 1

[15] Baltimore Sun, 1860/11/28, p1. There are other mentions of Tom Gorman in the Sun, and they will also be found in the American and the other newspapers of the day that are not available on line with ocr’d text indexes. This particular chase took place in the Northeastern Police District. Tracy Matthew Melton in Hanging Henry Gambrill. Baltimore, 2005, consulted all the extant newspapers for the period when Gorman was a detective, but did not mention him or his connection to the Plug Uglies and Know Nothings. The newspapers published in Baltimore between 1855 and 1865 are listed by Jean Baker, The Politics of Continuity, Baltimore, 1973, pp. 223-224, and William Evitts, A Matter of Allegiances, 1974, p. 198. Only the Baltimore Sun is adequately indexed on line. The Baltimore newspapers that will prove helpful to following Tom Gorman’s career, are the American, the Daily Gazette, the Baltimore Clipper (a Know Nothing newspaper), and the two German language dailies, Der Deutsche Correspondent and Baltimore Wecker. Images of the American (various titles) and the Der Deutsche Correspondent are on line through Google, https://sites.google.com/site/onlinenewspapersite/Home/usa/md, while the surviving images of the Baltimore Clipper are available from the Maryland State Archives: M8521 - March 3, 1847 - December 31, 1863; M8522 - January 1, 1864 - December 31, 1864; M8523 - January 2, 1865 - September 30, 1865, and original scans presented in pdf format. Sadly, no reasonably accurate on-line ocr text generated index is planned for these newspapers, making it very difficult and time-consuming to trace individuals named in their pages. Generally speaking even if ocr text indexing is available based upon the microfilm, the results are spotty. As I tried to explain in the sample I provided on line of the American for 1814, the original newspapers that have survived need to be scanned on flatbed scanners using a method I developed to preserve the paper when it is passed through the scanner and then ocr’d using ABBYY or some other good ocr program. I took sample images of the Clipper that had been scanned to the standard I set at MSA and ocr’d them with Abbyy myself at home. As a result I was able to locate quickly several articles that related to Tom Gordon that are referenced here. It is sad that Archival repositories that have original newspapers do not follow the example I set. It is in their best interest to do so.

[18] Frank Moore, The Rebellion Record, Vol 5, New York, 1866, p. 430. Images from the Baltimore Clipper will be added in the near future to this post with citations that will document Gorman’s difficulties following his probable ouster as one of Baltimore’s first detectives.

[20] It is not certain that this is the grave of Detective Tom Gorman from Baltimore. There is a Mary Gorman buried in this cemetery who died in 1866. Perhaps Tom had relatives in Wilmington who he was visiting when he died in 1863, or perhaps this is another Thomas W. Gorman, although the coincidence of the Baltimore reference, and the age of the deceased, strongly suggests it may very well be the detective.

[22] William J. Evitts,A Matter of Allegiances: Maryland from 1850 to 1861. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974, Jean H. Baker,The Politics of Continuity; Maryland Political Parties from 1858 to 1870. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973, and Ambivalent Americans: The Know-Nothing Party in Maryland. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977, Tracy Matthew Melton,. Hanging Henry Gambrill: The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, 1854-1860. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2005. For anyone interested in the history of the Baltimore police before the Civil War see the topical analysis of the surviving records in a public archives at: https://baltimorecityhistory.net/police-records/. Also it has been brought to my attention that for the Southern District the desk sergeant's log of events in that district for 1850-1853 is available in Special Collections at the Albert O. Kuhn Library. See: HV8148.B2 B35 1851.